Unlock the Secrets of Your Skin: Discover How It Mirrors Your Health

Our recent discussions have highlighted the skin’s ability to reflect a variety of medical conditions, with a particular focus on eczema and psoriasis. This article underscores the skin’s critical role as our body’s largest organ, capable of revealing much about our overall health. As we delve deeper, we’ll uncover the dynamic functions of the skin, from protection to disease prevention, and understand why it’s truly the window to our well-being.

Guard Your Life by Taking Care of Your Skin

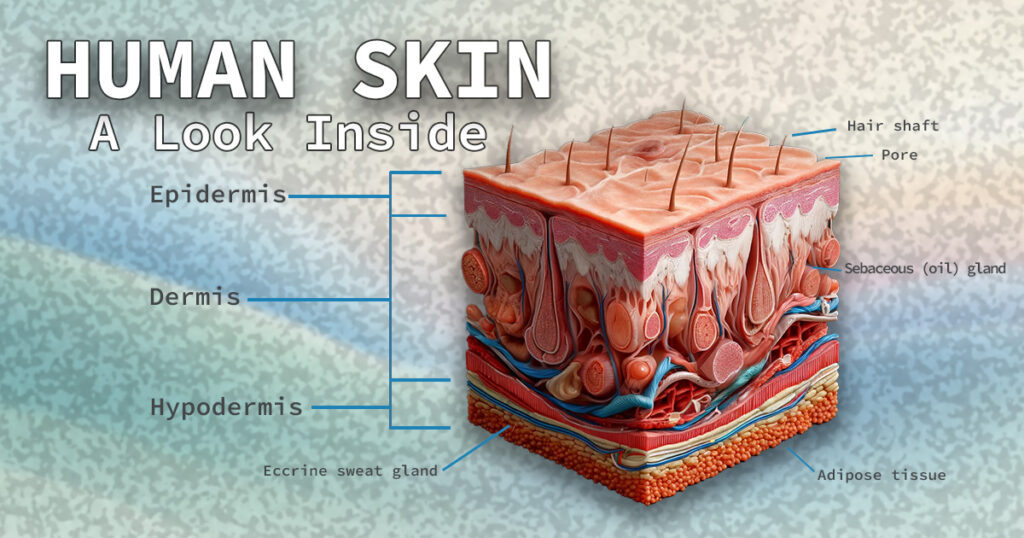

The skin is not just a protective sheath; it’s an active, dynamic organ of elimination that often reflects internal issues, from stress and anxiety to more complex systemic problems. Enveloping the entire exterior of our bodies, the skin acts as the frontline defense against a host of potential threats, including microorganisms, dehydration, ultraviolet light, and physical injuries. Our skin is a complex three-layered barrier that protects us from external threats and mirrors our internal well-being. Let’s unravel the intricate layers of the skin and their functions.

- Epidermis: the outermost layers of skin and your first line of defense against germs, bacteria, and other harmful substances.

- Dermis: found beneath the epidermis, contains connective tissue, hair follicles, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and sweat glands.

- Hypodermis: The deeper subcutaneous tissue made of fat connective tissue.

Before we begin dissecting the various layers of the skin, let’s review a few key terms that will help us better understand the article.

- Adipose tissue—commonly known as body fat—is a connective tissue made up of adipose cells that produce and store fat globules. Adipose tissue is present in various parts of the body. It can be found directly under the skin as subcutaneous fat, surrounding internal organs as visceral fat, and inside bone cavities as bone marrow adipose tissue. It can also be present between muscles, within the bone marrow, and in breast tissue.

- Blood vessels are the arteries, capillaries, and veins that deliver blood and oxygen to vital organs and remove waste products.

- Collagen – The primary building block of skin, muscle, bones, tendons, ligaments, cartilage, and hair.

- Connective tissue—Dense, fibrous tissues made of collagen and elastin that support, protect, and give structure to other tissues and organs in the body.

- Elastin is one of the most abundant proteins in your body. It is a stretchy protein that resembles a rubber band. It can stretch out and shrink back. Elastin is a major component of tissues requiring stretchiness, such as your lungs, bladder, large blood vessels, and ligaments.

- Fibroblasts – a type of cell that produces collagen.

- Lymphatic vessels help regulate fluid levels in the body, receive waste products from tissues, and transport fluid called lymph that defends the body against infections.

- Visceral fat – is a type of fat found deep within the abdominal cavity. It surrounds vital organs, including the stomach, liver, and intestines, and is the most dangerous to health.

The Epidermis: Your Skin’s Shield

The epidermis is the outermost layer of your skin, and despite being the thinnest, it plays a pivotal role in your body’s defense system. Think of it as your personal bodyguard—it keeps harmful microbes, chemicals, and UV rays at bay, protecting your inner layers and bloodstream from potential infections. This protective barrier is also crucial in preventing dehydration and managing your skin’s hydration levels.

The epidermis varies in thickness depending on where it is on your body—it’s as thin as 0.05 mm on your eyelids, making them delicate to touch, and as thick as 1.5 mm on the palms of your hands and soles of your feet, where durability is needed most.

A Closer Look at the Layers of the Epidermis

Stratum Basale: This foundational layer lies at the base of the epidermis. It’s where your skin tone gets its color from melanocytes, the cells that produce melanin pigment. This layer is also bustling with activity as new skin cells are born here. It houses keratinocyte stem cells, which generate keratin—a protein that forms your skin’s rugged outer layer as well as your hair and nails.

Stratum Spinosum: Often referred to as the “spiny layer” due to the spine-like appearance of the cells, this layer sits just above the stratum basale. It’s rich in keratinocytes bound together by desmosomes—special proteins that strengthen your skin and enhance its flexibility.

Stratum Granulosum: Located between the stratum spinosum layer and the stratum lucidum layer, this layer acts as your skin’s waterproofing seal. The cells here contain dense basophilic keratohyalin granules that release lipids and work alongside the desmosomal connections to create a water-resistant barrier that locks in moisture and keeps harmful substances out.

Stratum Lucidum: This layer lies between the stratum spinosum layer and the stratum lucidum layer. Found only in the thicker skin of your palms and soles, this thin, clear layer helps reduce friction, allowing the outer layers of the skin to glide over each other smoothly. The cells in this layer are flat and densely packed, optimized for protecting the layers below. The name itself comes from the Latin for “clear layer,” which describes the transparency of its cells.

Stratum Corneum: The topmost layer of the epidermis, also known as the “horny layer,” is your foremost protector against the outside world. It consists of dead skin cells that are tough and water-resistant, providing a strong barrier against environmental threats while preventing moisture loss. This layer is continuously shedding, renewing your skin’s surface. Most areas of the stratum corneum are about 20 layers of cells thick. Areas of skin like your eyelids can be thinner, while other layers, such as your knees and heels, may be thicker.

Understanding the epidermis in detail reveals just how dynamic and vital this skin layer is in protecting and maintaining the body’s delicate balance.

The Dermis

The dermis is the middle layer of the skin, primarily composed of fibrous tissues, including collagen and elastic fibers. It consists of two distinct layers: the papillary dermis and the reticular dermis.

Papillary Dermis (PD)

The papillary dermis is the upper, thinner layer of the dermis, located directly beneath the epidermis. It is significantly thinner than the reticular dermis. This layer comprises collagen fibers, connective tissue, blood vessels, fibroblast cells, fat cells, nerve fibers, touch receptors such as Meissner corpuscles, and phagocytes. Meissner corpuscles are specialized nerve endings that relay information about fine touch and vibrations, enhancing our ability to discern textures and shapes. Phagocytes are cells that can engulf and absorb bacteria and other particles, playing a crucial role in immune response. The papillary dermis forms a strong, interlocking bond with the basement layer of the epidermis, supporting two primary functions:

- It supplies the epidermis with essential nutrients.

- It facilitates thermoregulation, the process by which the body maintains its core internal temperature.

Reticular Dermis (RD)

Located beneath the papillary dermis, the reticular dermis is the thicker, lower layer of the dermis. This layer contains blood vessels, glands, hair follicles, lymphatics, nerves, and fat cells. It is characterized by a network-like structure of elastin and collagen fibers that support the skin’s structural integrity, enabling it to stretch and move flexibly. The functions of the reticular dermis are diverse and crucial for various sensory and physiological processes:

- It is integral to the sensation of touch, allowing us to feel various stimuli such as pressure, pain, heat, cold, and itchiness.

- It produces hair across most of the skin, except for the palms of hands and the soles of feet.

- This layer is where the body produces sweat in response to heat or stress, which helps regulate its temperature.

- The sebaceous glands within this layer secrete sebum, an oily substance that helps keep the skin and hair moisturized and lustrous.

Together, these layers of the dermis play vital roles in protecting internal structures, sensing the environment, regulating temperature, and maintaining overall skin health.

The Hypodermis

The hypodermis, also known as the subcutaneous layer, is the innermost layer of the skin, situated beneath the dermis. It comprises a variety of components, including fibroblasts, adipose tissue, connective tissue, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, hair follicles, sweat glands, and nerves. This layer is crucial for storing most of the body’s fat, which serves as insulation against cold and as a cushion to protect internal organs from shock and damage.

Functions and Characteristics of the Hypodermis

The hypodermis provides essential structural support to the skin, helping to shape and contour the body. It tends to be thickest in specific areas: in males, it is predominantly found in the abdomen and shoulders, whereas in females, it is more pronounced in the hips, thighs, and buttocks. As individuals age, the hypodermis decreases in size, which can result in skin sagging. This thinning increases the risk of hypothermia due to reduced insulation and diminishes sweating, potentially leading to heat-related illnesses like heat exhaustion and heatstroke.

Health Implications Due to a Comprimsed Hypodermis

The fat stored within the hypodermis is known as subcutaneous adipose tissue, distinct from visceral adipose tissue that lines internal organs. An excess of fat in these areas can contribute to obesity. Additionally, this layer is prone to the development of bedsores or pressure ulcers, particularly in individuals who are bedridden or frequently use a wheelchair. These open sores can extend deep into the hypodermis due to sustained pressure on the skin.

Panniculitis

Another significant condition affecting the hypodermis is panniculitis, an inflammation of the subcutaneous fat. This condition presents as hardened nodules or plaques on the skin, typically affecting the shins and calves before possibly spreading to the thighs and upper body. While panniculitis is rare and generally resolves within six weeks—and thankfully—without leaving scars, it can also cause symptoms like swelling, redness, bruising, and joint pain.

Possible causes of panniculitis include:

- Severe viral or bacterial infections

- Inflammatory diseases like inflammatory bowel disease, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis

- Certain antibiotics

- Birth control pills

- Sarcoidosis (a rare disease that causes granular lumps in tissues)

- Blood cancers like leukemia or lymphoma

Hypodermis Exposure Risks

Although the hypodermis is the innermost layer of skin, it is exposed when third-degree burns or severe lacerations destroy the epidermis and dermis. This exposure can lead to significant fluid and heat loss, increasing the risk of life-threatening conditions, severe bacterial infections, and permanent nerve damage.

Additional Roles of the Hypodermis

Beyond its primary functions, the hypodermis plays a vital role in:

- Storing energy in the form of fat

- Connecting the dermis to underlying muscles and bones

- Insulating the body and providing protective padding

- Supporting the function and structure of nerves and blood vessels within the skin

- Protection from heat exhaustion and heatstroke

As you can see, the hypodermis is critical for the skin’s structural integrity and thermal regulation, playing a vital role in health and disease management within the body.

Five Steps for Caring for Your Skin: Embrace Its Heroic Role

Your skin is your largest organ and your primary shield, protecting you from the external environment. This complex and vital organ is an unsung hero that merits heroic treatment. To maintain its health and vitality, consider the following six tips:

- Stay Hydrated: Drinking plenty of water is crucial for keeping your skin hydrated. Proper hydration helps maintain skin elasticity and can reduce the appearance of wrinkles, scars, and fine lines.

- Eat Healthily: What you eat directly impacts your skin’s health. A balanced diet rich in vitamins and minerals will promote a clear, glowing complexion.

- Stay Active: Regular physical activity improves lymph drainage—essential for maintaining healthy skin. A well-functioning lymphatic system helps prevent congestion and swelling, enhancing your skin’s overall health. To learn more about lymph drainage and your lymphatic system, please read my article “Signs of an Unhealthy Lymphatic System and What to Do.”

- Reduce Stress: High stress can negatively affect your skin, triggering flare-ups of various skin conditions. Stress-reducing activities such as meditation or yoga can significantly benefit your skin health.

- Pamper Your Skin: Treat your skin with the gentleness it deserves. Avoid drying it out with long, hot showers; instead, opt for shorter baths with warm water and gentle patting instead of harsh scrubbing. Your skin is as vital an organ as your liver or kidneys. It deserves the same level of care and attention. Remember to treat your skin with the utmost care to keep it healthy and glowing.

I hope you found this article helpful. Please share it with someone who you think may be blessed by it. As always, take care of yourselves and have a happy healing. See you next time.